Yeast: the Invisible Winemaker

Yeast is a fascinating microorganism, a true workhorse in the culinary world.

Yeast is fundamental to a vast array of our favorite foods and drinks, as evidenced by the burgeoning popularity of fermented beverages, lauded for their potential probiotic and gut-healthy benefits. From bread to kombucha, beer, pizza, and of course, wine, yeast plays a pivotal role in a process called fermentation.

In making wine, plus beer, spirits, and all alcohol beverages for that matter, fermentation is the process where yeast consumes sugars and carbohydrates to produce alcohol, carbon dioxide and heat as byproducts. In winemaking, the yeasts are simply converting the sugar in the fruit to create alcohol and CO2, the latter of which creates bubbles in sparkling wine.

While yeast’s influence extends far beyond the vineyard, it is undeniably on of the most important parts of winemaking. Without it, the grapes and their juice would remain just that: unfermented juice.

Let’s get our hands dirty with yeast and its use in winemaking.

What Exactly is Yeast?

Yeast cells close-up (courtesy of Wikipedia).

Yeasts are single-celled, microscopic organisms which are all around us, yet invisible to our naked eye. They are crucial for the fermentation processes that produce many of our favorite foods and beverages.

There are thousands of yeast species with saccharomyces cerevisiae being the main primary force force winemaking. Think of yeast as tiny workers within foods, fruit, grains, etc., that allow a transformation to then create another food and beverage. Think of them like nature’s miracle workers.

In winemaking, yeast consume sugars in grape juice to create alcohol, and then release a range of compounds that contribute to a wine's aromas and flavors, such as fruity esters, which enhance the complexity, and appeal, of a wine. In short, yeast is a living microorganism and an essential and active participant in winemaking that can fundamentally shape the final product’s characteristics like flavors and aromas.

Where Do We Find Yeasts?

“Bloom” as seen on a red grape cluster. The dusty look to the grapes are actually partially yeasts.

Native Yeast

There are actually a lot of native yeasts that reside naturally in the vineyard, in its surrounding environment outside, as well inside winemaking facilities, like wine cellars.

In the vineyard, yeasts live on the skins of the grapes, forming a powdery film known as the bloom, and are also present in the air, meaning they can hitch a ride on equipment and people to also spread all over the winery itself.

As grapes are harvested and crushed, these wild yeasts will come into contact with the juice and, under the right conditions, spontaneously initiate fermentation in what is called, understandingly, spontaneous fermentation.

All of the above are known native, or indigenous, yeasts.

Yeast Additives

Most wines you find “around” in supermarkets, etc, are made with the addition of yeast. Think of it like a yeast starter for when you make bread. As we discussed in this mother dough recipe article, you could actually create your own natural yeast starter to make bread dough, or you can buy a packet of yeast to allow for the bread to ferment, i.e., rise.

Winemaking has become such a standardized process, especially for wines made for a mass market audience which are the large majority of wines you find around the USA. As a result, it has become commonplace for most wines to be made through the use of yeast additives. In this case, winemakers add commercially cultivated strains of yeast to the freshly pressed grape juice so to allow for more control both over the winemaking process and the final outcome of the wine itself, e.g., its taste and appearance.

Commercially produced wine yeasts are specific strains of saccharomyces cerevisiae and other species that have been carefully selected and cultivated in laboratory settings for their predictable characteristics and their ability to impart specific flavor and aroma profiles to the wine. This means by using selected yeasts, winemakers can be much more in control of the end product and ensure it is the same year after year.

The Pros and Cons of Adding or Not Adding Yeast

Winemakers have a critical decision to make when grapes arrive in the winery after harvest: rely on spontaneous fermentation, in other words, using only native yeasts which are naturally present in their vineyards and winery for spontaneous fermentation, versus inoculation, meaning to add yeast, like a commercially available yeast strain to inoculate their grapes, thus allowing for fermentation.

Which approach chosen often reflects a fundamental philosophy to a winemaker’s style and beliefs.

The No Additives Approach

Those who champion spontaneous fermentation are typically those who are not making wine “in an office”, and instead make wines relying solely on what nature provides: they prefer their wines to have its terroir shine through, and by relying only on native yeasts is major contribution to this winemaking style.

They believe that these local yeasts, having evolved in the specific environment of the vineyard, can imbue the wine with distinctive aromas, flavors, and a textural integration that commercially produced yeasts may not replicate; aromas, flavors, and textures that are designed by the local environment. Think of the subtle herbal notes or the distinctive minerality that can sometimes characterize wines made with native yeasts. Proponents of native yeast fermentation think that these are expressions of the vineyard's unique microbial fingerprint.

Furthermore, there's a tactile element often associated with native yeast fermentations, a sense of the wine being more harmoniously integrated, leading to a more seamless and nuanced wine and food pairing experience.

Then there’s the practical advantage that you don't necessarily have to buy yeast; the vineyard provides its own. As winemaker Andrea Ivaldi says, “Why incur extra costs buying something that my vineyard and winery naturally produce on their own?”

Fermenting red grapes with native yeast at the Case Corini natural winery.

Why Add Yeast to Wine?

Conversely, winemakers who opt for inoculation with commercial yeasts often prioritize control, consistency, and predictability. These carefully selected strains are known for their reliable fermentations, and their capacity to enhance specific aromatic or structural components in the wine. There are certain strains marketed for certain wines, such as “pinot noir yeast”, that actually give boosts to certain aromatic and flavor compounds to make the wine “more” like a certain expected stereotype.

This is a "hands-on" approach to winemaking, molding a final product, rather than crafting it. These yeasts will indeed provide a winemaker with a greater degree of certainty of the outcome in the winemaking process, ensuring a consistent product from vintage to vintage. This is particularly crucial for wineries aiming for a specific style or for those operating on a larger scale where uniformity (and conformity) is paramount. But it will eliminate all the native yeasts and local flavor from a wine.

It’s Not Always Sunny with Native Yeasts

Now, the connection between native yeasts and terroir is a compelling one. Research suggests that individual vineyards can indeed harbor distinct populations of yeasts, creating unique ecosystems based on their individual biodiversities. These yeast biomes can vary not only between distant regions like Piedmont and Burgundy but also within smaller geographical areas and vineyards themselves. However, while the allure of expressing terroir through native yeasts is strong, relying on spontaneous fermentation is not without potential pitfalls.

If fermentation is not carefully monitored, the very diversity of wild yeasts can sometimes lead to unpredictable outcomes. In certain instances, less desirable yeast strains might dominate in the early stages of fermentation, potentially producing malodorous compounds that will necessitate intervention and course correction by the winemaker. However, with established wineries that have practiced spontaneous fermentation for years, a form of natural selection often occurs, favoring beneficial yeast populations and making such negative outcomes less likely over time.

Winemaker Guido Corino of natural winery Case Corini checking on his fermentation tanks making sure the yeasts are behaving as they should.

As well, remember how we mentioned that spontaneous fermentation is sparked partially by yeasts already present in the winery and cellar. This poses a different type of issue for newly established wineries. Unlike older estates where years of harvests have introduced and cultivated a resident population of vineyard-derived yeasts throughout the winery, these nascent operations may lack the necessary microbial biodiversity to initiate a successful spontaneous fermentation. The "hitchhiking" yeasts simply aren't present in sufficient numbers. In such cases, relying solely on native yeasts might lead to a stalled or incomplete fermentation, compelling the winemaker to introduce commercial strains to ensure the wine is properly produced. So, sometimes, a winemaker doesn’t have a choice, at least in the beginning, but to use commercial yeasts.

Sometimes winemakers must also be forced to add extra yeasts because what is present in the vineyard is not strong enough to eat all the sugars present. This is a problem in grapes that can have a tendency to produce lots of sugar, but is becoming more an issue with climate change. In fact, Aldo Clerico, a renowned Barolo producer whose usual approach is to rely solely on native yeast to ferment his red wines, has experienced firsthand the impact of climate change on his Barbera d’Alba. The warming temperatures has led, on occasion, to stalled fermentation of his Barbera wine because native yeasts struggled to complete the fermentation process. Aldo would like his Barbera to be a dry red wine, so he has decided in this case to add yeasts to ensure the wine ferments fully to dryness, with no residual sugar.

All of this ties into the fact that while we may really love the concept of terroir that native yeasts gives us, there are practical limitations to relying solely on Mother Nature (she takes as she gives away). Sometimes things like vineyard location can even play a part. Maybe a hillside vineyard with better drainage and airflow might foster a different spectrum of yeast species compared to the more humid conditions of the flatlands, potentially influencing the resulting wine's aromatic complexity and overall character.

Sometimes a winemaker who wants to only use native yeasts might try with all their power to spontaneously spark a fermentation. But thanks to the uniquely complicated world of winemaking:

the wrong strain could take off and then they must correct it;

or fermentation may stop too soon and there is residual sugar that shouldn’t be there;

or maybe they can’t get fermentation to start at all.

Yet, as we said earlier, the choice to use or not use native yeasts reveals a philosophical winemaking divide:

does the winemaker just blast their wine with commercial yeast to head problems off at the pass;

or do they try to work with their vineyard, grapes and winery, course correcting and adjusting their techniques as only necessary by the vintage?

Do they work with their wine and grapes;

or do they try to force their grapes into a cookie cutter mold?

It really comes down to you, the wine buyer and the wine drinker, to decide on which is the preferred approach.

Lees and a Post-Fermentation Legacy of Yeast

There is one last curiosity that can come from yeast, and that is once fermentation is actually complete. The yeast cells, having fulfilled their role, begin to die and settle at the bottom of the fermentation container. A sediment is formed which is known as the lees. Far from being waste, lees are actually really important and can significantly impact the final characteristics of the wine.

Fermenting white wine grapes at Case Corini natural winery.

A winemaker can choose to allow a wine to remain in contact with its lees, in a process known as "lees aging" or "sur lie”. This can create several results; as the yeast cells break down (a process called autolysis), they will release various compounds into the wine that will contribute to a richer, more complex mouthfeel, adding body and texture. Flavors and aromas will also be “created” so to speak, and contact with the lees can introduce intriguing notes of bread dough, pastry, or even a subtle nuttiness to a wine. Think of the characteristic brioche notes often found in traditional method sparkling wines, which can gain much of their complexity from extended lees aging.

Winemakers who follow this approach, may decide:

to do lees aging in the wine vessel for a certain amout of time as it is maturing, as Quercia Scarlatta does with their white wine blend, Marchese Japo;

to bottle ferment & age with the lees and then disgorge, as they do with champagne style wines, like Sandro de Bruno with their Durello classic method sparkling wine and Ivaldi Dario and their Alta Langa Chardonnay traditional method sparkling wine;

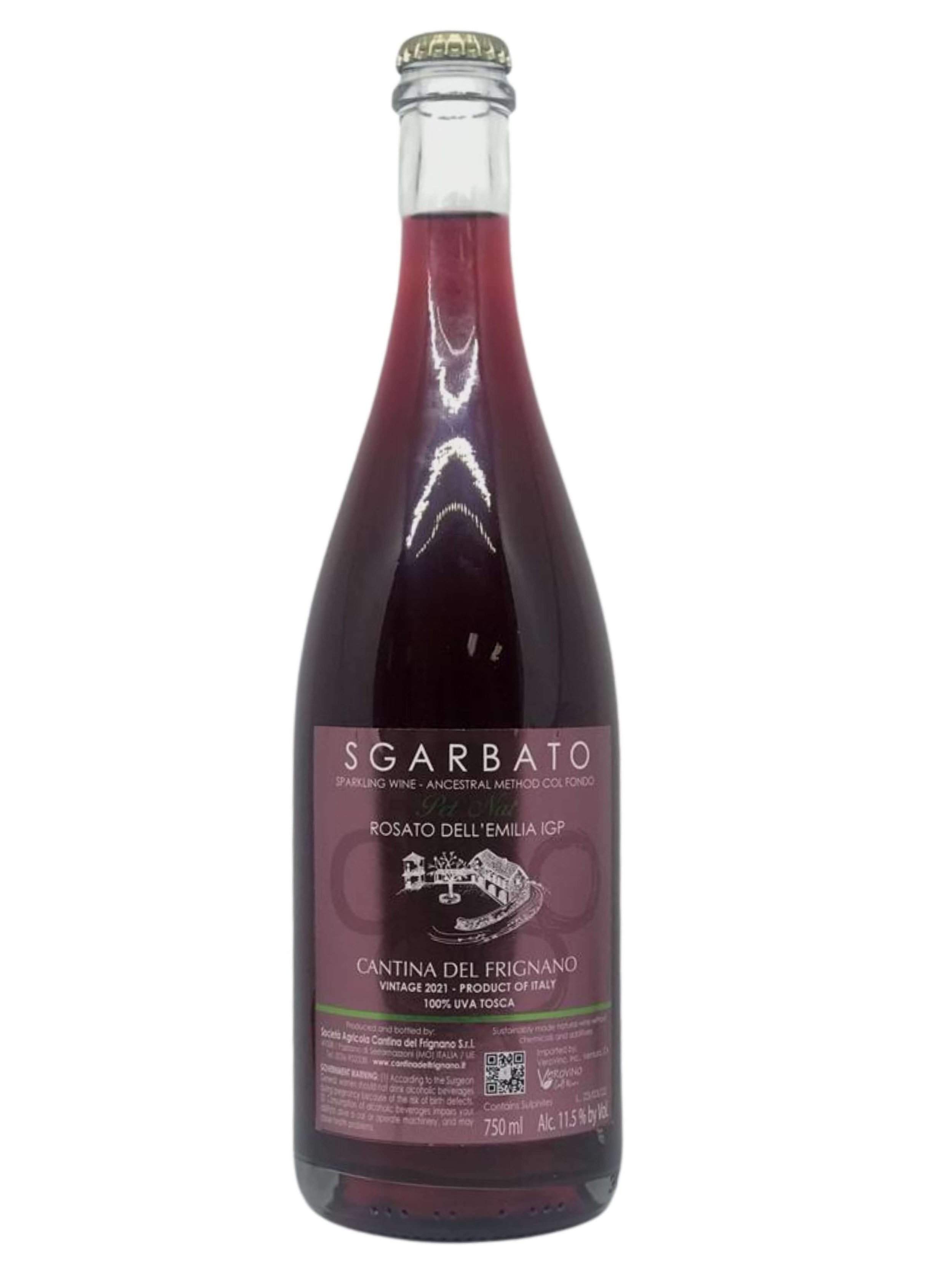

or they may bottle ferment and leave the wine on its lees in the bottle to age until opened and poured, becoming essentially an unfiltered champagne style wine; these wines are known as Pet Nat, Ancestral Method or Col Fondo sparkling wines. A wine producer who makes wines exclusively using this method is Eros Zanon.

The Art and Science of Yeast in Winemaking

Ultimately, the choice between spontaneous fermentation and inoculation with commercial yeasts is a complex one, often influenced by the winemaker's philosophy, the specific goals for the wine, the characteristics of the vineyard, and even the vintage conditions. In reality, there is no single "right" way, and both approaches can yield exceptional wines.

Winemakers who embrace native yeasts often see themselves as stewards of their land, allowing their unique terroir to express itself authentically in their wines. Consequently, they must accept a degree of vintage variation as an inherent part of this natural process (many, like us, view this as a good thing). On the other hand, winemakers who opt for commercial yeasts generally prioritize control and consistency, aiming for a predictable and reliable outcomes year after year.

Regardless of the chosen path, the humble yeast remains an indispensable partner in the journey from grape to glass. These microscopic fungi are the unsung heroes of winemaking, silently working their magic to transform simple sugars into the complex tapestry of flavors, aromas, and textures that we so appreciate in a well-crafted wine. Just as yeast is essential in the airy structure of pizza dough and the tangy profile of naturally leavened bread, it is the very lifeblood of wine, a testament to the power of nature's smallest yet most impactful players.

“Bloom” as seen on a white grapes.

Now it’s time to experience the pleasures of wines made from native yeasts, like our curated small production, farm to glass wines which we sell across the US, to both businesses and consumers.

How can you get your hands on these hidden gems we forage for?

If you are a distributor reach out to us introduce our highly curated portfolio of one of a kind small production wines to your state.

We sell to wine stores and restaurants in certain states - contact us to learn more.

If our farm crafted natural wines and olive oils are not in your local shop or restaurant, buy wine online here, and we’ll ship it to you, including wine gifts.

We also have an award winning wine club for true wine explorers that are seeking to continually discover unique, sustainable and authentic small production wines they never had. These are wines selected by our sommeliers and curated for each box.

We do corporate gifts and sommelier guided wine tastings. Email us and we’ll tailor unique and sustainable corporate gift ideas.